Global shipping logistics has gotten complicated with all the vessel types, trade routes, and chokepoint concerns flying around. As someone who’s tracked ocean freight for years, I learned everything there is to know about how this vast system actually works. Today, I will share it all with you.

Every day, more than 50,000 merchant vessels crisscross the worlds oceans carrying 90% of global trade. From the smartphone in your pocket to the fuel in your car, almost everything you own traveled by ship at some point. Understanding how this system works reveals the hidden infrastructure of modern life.

The Scale of Global Shipping

The numbers are staggering. The global merchant fleet comprises approximately 100,000 vessels with a combined capacity exceeding 2 billion deadweight tonnes. These ships carry 11 billion tonnes of cargo annually, worth over $14 trillion.

Container ships alone transport goods worth $4 trillion each year. The largest container vessels carry 24,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) — enough to stretch 90 miles if the containers were placed end to end. Probably should have led with this section, honestly.

Types of Cargo Ships

Different cargoes require specialized vessels optimized for their particular needs.

Container Ships

The workhorses of global trade, container ships revolutionized shipping in the 1960s by standardizing cargo into uniform boxes. Modern ultra-large container vessels (ULCVs) are the largest ships ever built, stretching 400 meters long and 60 meters wide.

Containers come in standard sizes: 20-foot (TEU) and 40-foot (FEU). Refrigerated containers (reefers) carry perishables at controlled temperatures. Tank containers transport liquids. The standardization allows seamless transfer between ships, trucks, and trains. Thats what makes containerization transformative — its about intermodal compatibility, not just ocean transport.

Bulk Carriers

Bulkers transport unpackaged dry commodities: iron ore, coal, grain, bauxite, and cement. Their simple design — large holds with hatch covers — makes them economical for high-volume, low-value cargoes.

The largest bulkers, Valemax class, carry 400,000 tonnes of iron ore from Brazil to China. Smaller handysize and supramax bulkers serve regional trades and ports with depth restrictions.

Tankers

Oil tankers range from small coastal vessels to very large crude carriers (VLCCs) holding 2 million barrels of oil. Product tankers carry refined fuels and chemicals in multiple segregated tanks.

Double-hull construction, mandated after major oil spills, provides environmental protection. Inert gas systems prevent explosive atmospheres in cargo tanks.

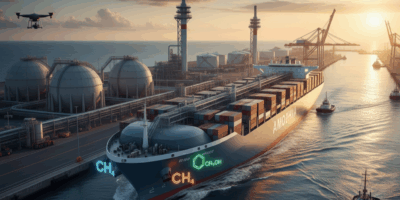

LNG and LPG Carriers

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) carriers maintain cargo at -162°C (-260°F) in specialized insulated tanks. The ships themselves often use cargo boil-off as fuel. Growing LNG trade has made these specialized vessels increasingly important.

Roll-On/Roll-Off (RoRo) Ships

RoRo vessels carry wheeled cargo that drives aboard via ramps: cars, trucks, trailers, and heavy equipment. Pure car carriers (PCCs) transport thousands of automobiles in multi-deck garages.

How Shipping Routes Work

Ocean shipping follows established trade lanes optimized for efficiency, weather, and geography.

Major Trade Lanes

The Asia-Europe trade lane moves manufactured goods westbound and machinery, chemicals, and raw materials eastbound. Ships transit either the Suez Canal (saving 6,000 miles versus Africa routing) or Panama Canal for trans-Pacific connections.

The Trans-Pacific trade connects Asian manufacturing to North American consumers. Ships call at ports like Shanghai, Busan, and Ningbo before crossing to Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Pacific Northwest ports.

Intra-Asian trade has become the worlds largest container market as regional manufacturing supply chains integrate across multiple countries.

Strategic Chokepoints

Narrow straits and canals concentrate shipping traffic and create vulnerability:

- Strait of Malacca — Links Indian and Pacific Oceans, handles 25% of seaborne oil

- Suez Canal — Connects Mediterranean and Red Sea, 12% of global trade

- Panama Canal — Pacific-Atlantic shortcut, 5% of global trade

- Strait of Hormuz — Persian Gulf exit, 20% of global oil

- Bosphorus — Black Sea access, critical for grain exports

When any chokepoint faces disruption — whether from drought, conflict, or accident — global supply chains feel the effects within weeks.

Port Operations

Major container ports move millions of TEUs annually. Shanghai leads globally with over 47 million TEUs. Singapore, Ningbo, Shenzhen, and Busan follow in the top five.

Modern container terminals use automated stacking cranes and driverless transport vehicles. Ships discharge and load simultaneously using multiple gantry cranes. Turnaround times of 24-48 hours are common for large vessels.

Bulk terminals handle commodities with different equipment — grab cranes, conveyor systems, and specialized loaders. Tanker terminals use pipelines connecting to storage farms.

The Economics of Shipping

Freight rates fluctuate based on supply and demand. Container rates on the Shanghai-Los Angeles route have swung from $1,200 to over $20,000 per container depending on market conditions.

Charter markets allow cargo interests to hire vessels for specific voyages or time periods. Spot market rates reflect current conditions while forward contracts provide rate certainty.

Fuel (bunker) costs represent 50-60% of voyage expenses. Ships increasingly adopt slow-steaming to save fuel, extending transit times but reducing costs per container.